Creatine and Sports Performance Strength Power and Recovery

Introduction

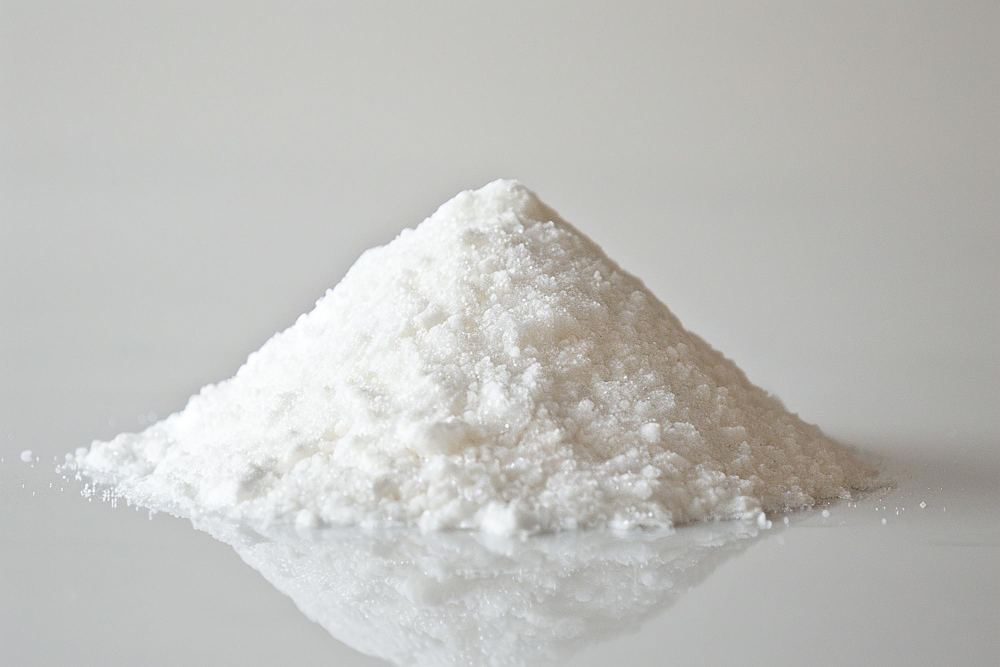

Creatine is one of the most extensively studied and widely used supplements in sports nutrition. Found naturally in red meat, fish, and produced by the body from amino acids, creatine is stored primarily in skeletal muscle as phosphocreatine. Supplementation boosts phosphocreatine stores, enhancing the ability to rapidly regenerate ATP—the body’s primary energy currency. This makes creatine particularly effective for short-duration, high-intensity exercise such as sprinting, powerlifting, and explosive movements.

Mechanisms of Action

- ATP Regeneration

- Phosphocreatine donates a phosphate group to ADP to resynthesize ATP.

- Increases capacity for high-intensity, short-burst activities.

- Training Volume and Adaptations

- Enhanced energy availability supports greater training volume and intensity.

- Leads to improvements in muscle hypertrophy, strength, and power over time.

- Cell Hydration and Signaling

- Creatine increases intracellular water, promoting cell swelling.

- This may act as an anabolic signal, supporting protein synthesis and muscle growth.

- Neuroprotective Effects

- Creatine may enhance cognitive performance under stress and fatigue.

- Emerging research suggests benefits in recovery from traumatic brain injury and neurodegenerative conditions, relevant for athletes in contact sports.

Research on Strength and Power

- A 2017 review in Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition concluded creatine is the most effective ergogenic aid for high-intensity, short-duration activities.

- Multiple meta-analyses show consistent improvements in maximal strength (e.g., bench press, squat), sprint performance, and repeated high-intensity exercise capacity.

- Adaptations are magnified over weeks, as creatine enables higher-quality training sessions.

Research on Endurance Performance

- Creatine is less effective for steady-state endurance.

- However, benefits may include improved sprint performance during endurance events and enhanced glycogen storage.

- Some studies show creatine may reduce inflammation and oxidative stress after prolonged exercise, indirectly aiding recovery.

Recovery and Injury Prevention

- Creatine may reduce markers of muscle damage and inflammation post-exercise.

- There is evidence for reduced incidence of cramping and heat-related illness, contrary to early myths.

- Recovery of strength after immobilization or injury appears faster with creatine supplementation.

Dosage and Timing

- Loading phase: 20 g per day (split into 4 doses) for 5–7 days to rapidly saturate muscle stores.

- Maintenance phase: 3–5 g daily thereafter.

- No loading option: 3–5 g daily, achieving full saturation in ~3–4 weeks.

- Timing is flexible, but taking creatine with carbohydrates and protein may enhance uptake via insulin-mediated pathways.

Safety and Side Effects

- Creatine is one of the safest supplements available, with decades of research showing no adverse effects in healthy individuals.

- Mild weight gain (1–2 kg) may occur due to increased water retention within muscles.

- Long-term studies (up to 5 years) show no harmful effects on kidney or liver function in healthy users.

Conclusion

Creatine remains the gold standard supplement for athletes seeking improvements in strength, power, and high-intensity performance. Its well-documented mechanisms, consistent research outcomes, and strong safety profile make it a cornerstone of sports supplementation. While not a direct endurance enhancer, creatine’s role in recovery, glycogen storage, and neuroprotection broadens its utility beyond just strength athletes. For performance and training adaptations, creatine is unmatched in evidence and reliability.

Sources

- Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Wildman, R., Collins, R., … Lopez, H. L. “International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Safety and Efficacy of Creatine Supplementation in Exercise, Sport, and Medicine.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 14, no. 1, 2017, p. 18. doi:10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z.

- Branch, J. D. “Effect of Creatine Supplementation on Body Composition and Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, vol. 13, no. 2, 2003, pp. 198–226. doi:10.1123/ijsnem.13.2.198.

- Chilibeck, P. D., Kaviani, M., Candow, D. G., & Zello, G. A. “Effect of Creatine Supplementation During Resistance Training on Lean Tissue Mass and Muscular Strength in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis.” Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 8, 2017, pp. 213–226. doi:10.2147/OAJSM.S123529.

- Cooper, R., Naclerio, F., Allgrove, J., & Jimenez, A. “Creatine Supplementation with Specific View to Exercise/Sports Performance: An Update.” Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 1, 2012, p. 33. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-9-33.

- Rawson, E. S., & Venezia, A. C. “Use of Creatine in the Elderly and Evidence for Effects on Cognitive Function in Young and Old.” Amino Acids, vol. 40, no. 5, 2011, pp. 1349–1362. doi:10.1007/s00726-011-0855-9.

.svg)